During Q2, the Fed stood in the background as it held rates steady while trade headlines dominated market moves. But entering Q3, the Fed is weighing its next move. The conundrum is that recent economic data, showing a solid economy and a continued slowdown in inflation, suggests additional rate cuts could be taken. Yet, saying “uncertain” 19 times in the most recent press conference, the Fed is still watching the data and trade policy talks to gauge the impact of tariffs on inflation.

The first issue is the data itself: Tariffs from April are not expected to show up in the economic data until June or July releases that are due throughout Q3, because businesses front loaded imports to beat the tariffs and thus products being sold in April and May were from non-tariffed inventories. On top of that, many of the announced tariffs have not been enacted for long enough to show up in the data, yet remain possibilities.

Second, the size of the potential inflation impact has added to the Fed’s cautious stance. When the U.S. enacted tariffs on China in 2019, the overall U.S. effective tariff rate went from just 2% to 3%. The Liberation Day tariffs, though not enacted, averaged over 20% across countries. After the U.S. and China declared a truce on their short-lived 100%+ tariffs in May, the effective U.S. enacted rate declined to “just” 13%. An easy rule of thumb for the impact of tariffs on inflation is that, since imports account for about 10% of U.S. consumption, a 10% effective tariff would increase prices by about 1%. That sounds small, but a 10-20% tariff rate equates to adding 1%-2% to the inflation rate, taking a 2% rate to 3% or 4%. With trade talks ongoing into July, this range of outcomes has to get factored into the Fed’s monetary policy plans. A move at its meeting at the end of July seems unlikely, but enough data and tariff deals could be in place for a September move, which will serve to increase the market’s focuses on these headlines.

Amidst periods of Fed policy focus, rather than predicting the Fed’s next move, we instead look to see if the bond market is pricing reasonable outcomes. If it is, then bonds can be a sensible option. If the bond market is unreasonably priced, it can set up investors for disappointment (or a major opportunity).

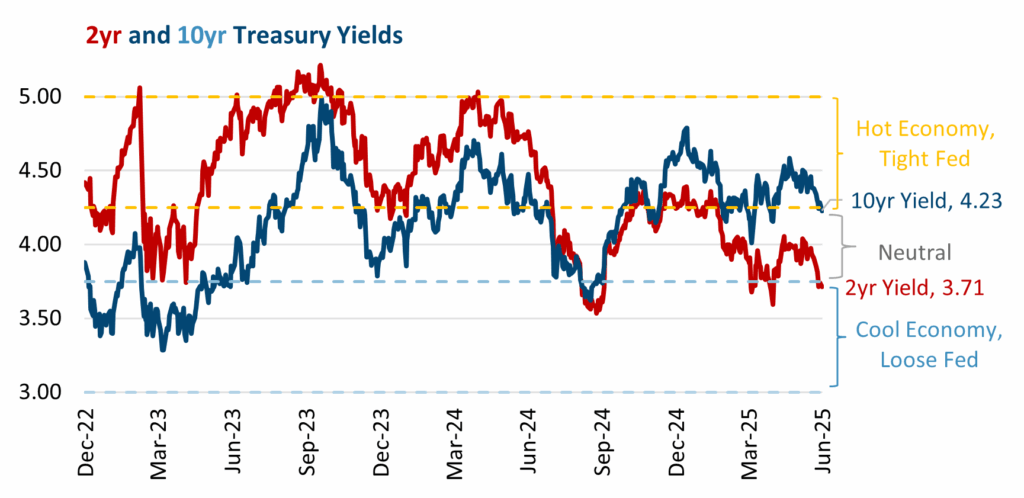

Assuming 2% inflation and 2% trend growth, we get a 4% neutral interest rate, bracketed by a 50 bps 3.75% to 4.25% neutral range. Chart 1 (below) shows the 2yr (Fed policy) and 10yr (economy), as well as orange “Hot Economy, Tight Fed” and a blue “Cool Economy, Loose Fed” ranges. The 10yr (at 4.23%, at the breakpoint between a Neutral and Hot Economy) and 2yr (at 3.71%, just pushing into the “Loose Fed” range) reflect a growing expectation that the Fed will be able to resume rate cuts soon. Currently at 4.25%, the still-consensus two 25 bps rate cuts in 2025 would take Fed Funds to 3.75%, not far from this level on the 2yr. We can also reverse the model’s logic to see where the Fed should “reasonably” have rates. With inflation (at least before tariff impacts) heading towards 2% and GDP growth at a solid 2%, you again arrive at 4%. If the Fed wanted to be mildly stimulative, then Fed Funds would be a few cuts below that, perhaps at 3.50%. Again, the positive (for the markets) is that the current 3.71% 2yr is not far from that level.

Chart 1

The implication is that, as Fed and interest rate headlines swirl, the market’s pricing of rates is reasonable on both Fed policy and the economic backdrop. This is not to say that interest rates are perfectly priced, but merely that they are not reflecting unreasonable expectations, and thus vulnerable to a major shift. It also means that if expectations build for an accelerated pace of rate cuts, that could bring the 2yr lower, as well as the 10yr, which would benefit duration sensitive bonds. On the other hand, if the likelihood of a rate cut falls or there is concern about tariffs pushing inflation higher, then duration sensitive bonds could be pressured by higher rates.

While the ongoing tariff overhang creates an element of uncertainty for Fed policy, another factor that could add to the market’s confusion during Q3 is the pending change of leadership. Federal Reserve Chairman Powell’s term is up in May of 2026, but by not cutting rates as quickly as hoped, he has garnered criticism. While there have been brief comments to “fire Powell,” a more likely path is for a “Chairman elect” to be anointed early, in which case the market will start to guess what that new leader will do. The January end to outgoing Federal Reserve Board Governor Kugler’s term would create an open seat for the new chairman, who must be a sitting member of that group prior to May.

Since markets are focused on Fed policy over the next six to 12 months, knowing that decisions in that timeframe could be under a different regime will start to make the new regime’s opinions more important. The incoming chairman’s prior comments, opinions, articles and papers will get parsed for clues. Senate confirmation hearings will certainly get coverage, too, let alone if the new appointee makes deliberate public comments on their policy plans.

This would create what’s known as a “Shadow Fed.” It’s not nefarious, but merely a government term for when an out of power party will have designees in place to comment on the policy actions of those in power. One example is a “shadow foreign minister,” who would seek to present an alternative policy from a minority party relative to a majority party’s actual foreign minister.

Why does this matter now? Since the January appointment requires Senate approval, the nomination process would get going three to four months before the date, and thus could be on the market’s mind as Q3 is closing. This will be at the same time the Fed is weighing a resumption of rate cuts at its September meeting, ideally with some clarity on tariff policy as well as a few more months of data to gauge the extent of the inflation impact thus far. This is enough uncertainty for the market to account for. If there are questions on who the true Fed spokesperson is, that could add volatility to the markets.

Fed independence is important: markets need to be confident the Fed will act as it sees appropriate to keep inflation under control, as well as the economy (as measured by unemployment levels) healthy. The ironic risk is that if a new Fed Chairman is selected with instructions to cut interest rates (or the market sees a bias to cut rates), it could undermine the market’s confidence that rates will be properly managed (even if the rate cut makes sense). This loss of confidence could, ironically, cause long-term interest rates to rise, even as the short-term rate is being cut.

Cumulatively, this means the two major macro drivers of tariffs and the Fed’s resumption of rate cuts are intertwined as we enter Q3. The good news is that if trade deals come through that are reasonable, it will bring clarity for the Fed to start acting. That, along with the broader clarity for the rest of the economy, would be a boost. The risk would be if tariff deals drag, the Fed gets held up, and the process of selecting the next Fed Chairman brings an added level of market uncertainty. Will the Uncertainty of Trade Policy be Obscured by a Fed Shadow?